TRANSCRIPT

DOWN TO EARTH: David Henkin ON MĀKUA

Earthjustice attorney David Henkin, longtime legal representative of Mālama Mākua

The transcript of the 2012 interview of Mālama Mākua legal representative and Earthjustic attorney David Henkin, as well as links to Earthjustice press releases which provide additional information, is below. If you would rather listen to the podcast, click on the player.

Earthjustice press secretary Kari Birdseye speaks with David Henkin, an attorney in the organization's Mid-Pacific office in Honolulu.

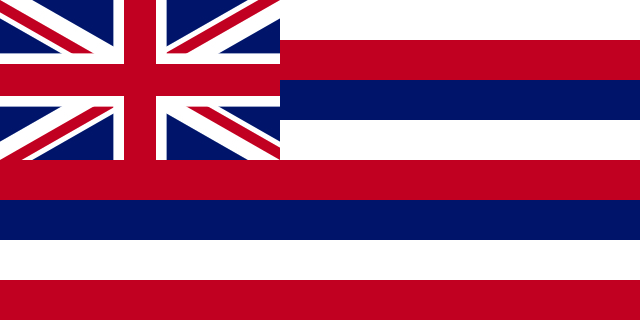

For almost two decades, Henkin has worked to force the U.S Army to stop live-fire training operations at the Mākua Military Reservation on Oʻahu. A culturally and ecologically important area, Mākua is home to scores of ancient Hawaiian artifacts, cultural sites and nearly 50 endangered plants and animals.

Kari Birdseye: How did we become involved with this military reservation?

David Henkin: We'd received some requests from the community on the Waiʻanae Coast, which is on the west coast of the island of Oʻahu. For many years, they had been concerned about the effects of live-fire military training on the cultural and biological resources of Mākua Valley as well as on the nearby communities.

Unlike military reservations in the continental United States or pretty much anywhere else that I've heard about, this live-fire training range is only about three miles from populated areas and the beach across the street from the military reservation is heavily used by area residents. People of modest income supplement the food that they provide to their families with fishing and gathering at Mākua beach and so folks were also concerned about potential off-site contamination associated with the military training and other activities.

For years they have been asking the Army to do an environmental review, which had never been done under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). And they had been asking the Army to do this, and the Army had refused. So they came and asked Earthjustice to assist them in getting a full disclosure of what the effects of live-fire training at Mākua are on the resources there and on the neighboring community, as well as an honest examination of what alternatives might be available to the Army to conduct the training in a more environmentally-responsibly manner.

Kari: So what'd you do?

David: Well, it takes some time to work up a case, so we spent some time investigating the facts and convincing ourselves that the Army did have an obligation under the law to do this environmental review. They had taken the position that since the training preceded the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act that they didn't have to do the review and our research convinced us that because it was an ongoing activity that they had to look at the impact. So this was not a situation where they had built some permanent structure decades ago and it was just remaining in place. It was training that over the years had changed.

And so we ended up filing suit initially in 1998 claiming that the Army had violated the National Environmental Policy Act by never doing any environmental review. And that resulted in a settlement agreement, the first settlement agreement, in 1999, in which the Army agreed that it would not do any training at Mākua until it had completed some form of review.

So under the National Environmental Policy Act, federal agencies are required to do environmental impact statements (EIS) in situations that pose the potential for a significant effect on the environment. And if they're uncertain if there's a potential for significant environmental effects, they can do a less comprehensive environmental assessment, which is mainly done just to figure out whether or not there is this potential for a significant effect.

And we said to the Army, "Well, you've got a track record here. It's been documented that you've burned up native forests, probably destroyed endangered plants, certainly bombed and destroyed native Hawaiian cultural sites." We didn't believe that there was any question but that they should prepare an environmental impact statement. The law, however, gives agencies the ability and right to start with environmental assessments, and they said they wanted to do that.

We said, "Well, we don't think it's a good use of your time or taxpayer dollars to go through this additional step, but you're allowed to do it under the law." So our agreement in 1999 said that the Army would do what it considered to be an adequate environmental review, and then, if it came out with an environmental assessment, they would continue the ban on training for an additional 30 days to give us a chance to get into court and argue that they needed to do the environmental impact statement, and that is ultimately what happened the following year in 2000.

Kari: If you can give me kind of a picture of what's going on there while the Army's there just to give some perspective on how the Army acquired this area, what kind of training they've done over the years, and then what's allowed after the settlement and to this day.

David: Sure, well, military presence at Mākua began in the late 1920s. It was a populated valley with a civilian population, but at that time in the late 1920s the Army secured a couple of small parcels to do some limited training. Things really changed dramatically after the attacks in Pearl Harbor in 1941. Martial law was declared in the Hawaiian Islands, and the entire western side of the island of Oʻahu, including Mākua, were taken by the military for military training. The families that had lived in Mākua for generations were evicted and were told that their lands would be returned six months after the cessation of hostilities. So, at the end of World War II the families expected that their lands would be returned to them, but that was not to be. The military has been in control of Mākua Valley ever since.

During the [19]40s, 50s, and 60s, all forms of live-fire training occurred at Mākua. They used the church in the valley as target practice, so that was destroyed with naval guns. They dropped 1000-pound bombs, 500-pound bombs, 100-pound bombs. All of these have been found to this day. They just cleared a 100-pound bomb out of the valley last year.

Kari: And in 2000, you went back and the agency was forced to do the full environmental impact statement at that time?

[The Army was] so bold as to have taken their original document and stripped out of it any statements that could be interpreted as an admission by them of a potential for significant environmental effect.

David: Well, what happened in 2000 was that they issued an environmental assessment and claimed that there was not even the potential for any significant harm to the environment. And we immediately went into court and challenged that, at which point they said, "Well, let's think about it a little bit more." So they withdrew that initial environmental assessment and said, "We're going to think about this and do another analysis."

They issued a revised environmental assessment with yet another "Finding of No Significant Impact," and they were so bold as to have taken their original document and stripped out of it any statements that could be interpreted as an admission by them of a potential for significant environmental effect. And indeed, they had attached to the document a biological opinion prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that listed 29 different endangered species that the service found were threatened with extinction if the Army did not substantially modify its training. And that document had been attached to the initial document that they came out with in 2000, and then it was attached to the revised environmental assessment. But, they had actually gone in and whited-out the phrase "likely to be jeopardized."

In other words, they took a list of 29 species that the service found were likely to be pushed to extinction by military training at Mākua, and they doctored it so that it no longer included the incriminating term, "likely to be jeopardized." It was a pretty blatant attempt to hide the potential effects of their training, which is completely contrary to the purposes of the National Environmental Policy Act, which is meant to be a law that requires agencies to be honest and to give full disclosure of what the possible effects of their actions are.

And so we continued with the litigation, and in July of 2001 we secured from the District Court a preliminary injunction. To my knowledge, this was the first time that a court had ever ordered the military not to train in an area because of violation of environmental laws. And I think this took the Army substantially by surprise. They expected that the court was going to allow them to resume training at Mākua while the case was going on, and the district court was quite firm that it felt that the potential risk to endangered species and cultural sites was demonstrated and the Army's claims that not being able to train at Mākua would somehow adversely affect national security were completely unsubstantiated.

So that was July of 2001. Shortly thereafter, the attacks of 9-11 [2001] occurred, and the Army became much more open to resolving the case and agreed to do the environmental impact statement in return for the ability to return to some limited live-fire training at Mākua. So in relatively short order, in a matter of less than three weeks, we negotiated a settlement agreement—pretty much a landmark settlement agreement in many respects.

We didn’t want the Army to drag this out indefinitely. We wanted the community to get the information that it had been asking for decades, and we wanted to make it clear to the Army that it would not be acceptable to us to allow low-level, live-fire training indefinitely at Mākua while they withheld the analysis the law required.

The Army committed to do a full environmental impact statement for its training at Mākua. We agreed that for a three-year period of time, the Army would be allowed to do a very limited number of live-fire exercises. The agreement further provided that if the Army did not complete the environmental impact statement within three years, that there would be no further live-fire training at Mākua until the analysis was completed. We didn't want the Army to drag this out indefinitely. We wanted the community to get the information that it had been asking for decades, and we wanted to make it clear to the Army that it would not be acceptable to us to allow low-level, live-fire training indefinitely at Mākua while they withheld the analysis the law required.

And then there were a number of additional components of this settlement agreement that were again, to my knowledge, the first of their kind. The agreement guaranteed that this low-income community would receive a technical assistance fund: $50,000 to hire outside experts to peer review the Army's studies because we wanted to make sure that the community had some independent basis to evaluate if the Army was doing its analyses properly. It provided for the Army immediately to start cleaning unexploded ordnance from the valley, which is something that normally the military does not do. They do not tend to clean unexploded ordinates from active live-fire ranges. They wait until those ranges are closed.

Also, because of the proximity between the live-fire training area and occupied areas, populated areas including beaches where people went to fish with their families, we wanted to make sure that any unexploded ordnance that posed a threat to the public outside of the boundaries of the reservation would be removed because if any of these munitions would accidentally detonate, they would be deadly for people traveling on the highway and at the beach park.

Over the years, the Army had not only fired mortars and artillery shells, but they've pulled 1000-pound bombs out of there, so we're talking some pretty heavy munitions. So this agreement required them to start cleaning that up to provide safety to the public. It required that they allow cultural access to Mākua's sacred sites at least two days a month and two overnights a year for celebration of the Hawaiian New Year.

Kari: So the final environmental impact statement talks about the native Hawaiian's stewardship and protection of the islands and is filled with traditional stories. Can you tell me about how this environmental impact statement came together and why there are these traditional statements included into this section?

David: When we started this process in the mid-to-late [19]90s, the Army's perception of Mākua was that it was a not very important area from a cultural perspective. The Army's theory was that Mākua, being a relatively hot and dry area, was not heavily populated by native Hawaiians prior to Western contact. It was just a few fishing huts down by the beach.

That was not a view that was shared by Mālama Mākua, our client, or other cultural practitioners in the area because of the significant stories, moʻolelo, in the Hawaiian tradition that are told about Mākua. Mākua means "parents" in Hawaiian and some of the beliefs that native Hawaiian practitioners share is that there are some origin myths in terms of the creation of people that are associated with Mākua and there are a number of very celebrated stories about the gods and their interaction with the people of Mākua.

And so it was our client's strong belief that we had a very incomplete story largely as a result of the Army's failure to do any type of environmental impact statement, which would require archeological investigation. And because since 1942 the area had been under constant military control with live-fire going on virtually non-stop, the Army's never really assessed the cultural resources.

So as a result of the settlement agreements, which required the Army to do the environmental reviews, we required that the Army do a comprehensive surface and sub-surface archeological investigation of the areas in which they trained at Mākua. That has led to a real sea change in terms of both the Army's and the broader society's understanding of the cultural significance of Mākua. We went from a situation where there were basically a handful of native Hawaiian cultural and archeological sites that were known to well over a hundred sites that are eligible for listing on the national historic register.

I think it was a wonderful example of why the law insists that federal agencies do a comprehensive environmental review of their actions. After the guns have stopped firing long enough to let the archeologists get out into the field, [it's clear] that this is a place of incredible cultural richness.

Through the archeological surveys, our Army has discovered countless Hawaiian temples and shrines and petroglyphs and house sites and agricultural features. And now the understanding of the valley is that it was, in fact, very heavily populated and that there was a rich and vibrant cultural life throughout the valley.

I think it was a wonderful example of why the law insists that federal agencies do a comprehensive environmental review of their actions because, again, the dominant thought back in the late 90s was that this was a cultural wasteland. And the dominant thought now in the 21st century, after the guns have stopped firing long enough to let the archeologists get out into the field, is that this is a place of incredible cultural richness.

During the comment period on the draft environmental impact statement, the community felt it was important to include within the environmental impact statement these moʻolelo, these stories, these tales of gods and their interactions with the people at Mākua. It's something that provides a more comprehensive understanding of the spiritual life of the valley.

From a Native Hawaiian perspective, there is not a sharp distinction between the cultural sphere and what we call the ecological sphere. People are part of nature, they interact with nature, and they have responsibilities to the plants, to the animals. They have familial relationships with some of the animals, spirit guardians.

And so our clients did not view the protection of the ecology as separate from the protection of the culture, and that's informed the work that we've done in the valley where we have made sure at every step of the litigation to emphasize to the court, and the court's been very responsive, that this is a living system. It's a system of people, it's a system of culture, and it's a system of plants and animals, and all of them need to be protected, all of them need to be respected.

Kari: You mentioned that community members are allowed to go on to the site for their cultural activities. Can you tell our listeners what those activities are and their cultural significance?

We have made sure at every step of the litigation to emphasize … that this is a living system. It's a system of people, it's a system of culture, and it's a system of plants and animals, and all of them need to be protected, all of them need to be respected.

David: Sure. First let me say that this is pretty unique situation in which cultural practitioners are guaranteed access to a live-fire training range to perpetuate and carry out their culture. At Mākua, there are a number of ancient Hawaiian temples, or the remains thereof, and shrines that the cultural access that occurs, occurs at least two day times per month and two overnights per year. Cultural practitioners and members of the community are allowed to go and reconnect with these sites.

If you think of the sites as a living being, the sites have cultural significance because of their interaction with people. So from a western archaeological standpoint, the Army was very concerned about people accessing sites because you might inadvertently step on a rock and move it. And so from the western archaeological, sort of museum perspective, that would be a harm to the site.

Well, the Hawaiian response is that it's not a harm to the site. If you inadvertently move a rock, you put it back. The harm to the site comes from cutting off its connection to people because a site that isn't used loses its mana, loses its spiritual force. And so, during these cultural accesses, people will come and bring offerings to the site. They will chant at the sites, and in that way reestablish the connection with the past, the connection with the culture. And in the absence of being able to have this personal interaction with these sites, they become just piles of rocks.

One of the things that Mālama Mākua was very committed to doing as part of the agreement that it reached with the Army would be to bring this spiritual life back to the valley. The notion here is that you don't just have a cultural connection with an individual site, but it's the land itself, it's the valley itself, the entire area, that you reconnect with.

Kari: Tell us a little about the plants and animals that are in this valley.

David: The Hawaiian archipelago is the most isolated island system in the world. We're the furthest from any continental landmass of any island system. And as a result, there's a high level of endemism, so a high level of plants and animals that are found in Hawaiʻi and nowhere else. And it goes down to an even more micro level. There are a lot of plants and animals that are found in one valley and nowhere else.

And so, at Mākua we find many, many species that are unique to the area. We have at Mākua a native flycatcher, the Oʻahu ʻelepaio, that relies on the forests that ring the valley. We have bejeweled tree snails. And then you have a variety of native Hawaiian plants, again, that are unique to the area.

During the course of the environmental review that was required under the settlement agreement, the Army has discovered many additional species of plants. There were entire species they were unaware existed at Mākua, including a population of our state flower, the Yellow Hibiscus. Right now the understanding is that there are about 45 federally listed plants and animals that are within what's called the action area, so the area that is at risk of burning up from training related fires.

The Army has finally acknowledged their existence and acknowledged the threats that live-fire training has posed to them. And as a result, they have undertaken a very extensive program of protection of the plants that are on site as well as out-planting in areas outside of the zone of influence of the live-fire training at Mākua. So, [they're] giving these basic building blocks of our native Hawaiian ecosystems an opportunity to persist into the future, be enjoyed by future generations, and also continue to play a part in the ecology of the area.

Kari: What about the water in and around the valley? Talk to the water issues in this case.

A key component of local culture, native Hawaiian culture, and other cultures that have come to Hawaiʻi, is the ability to gather from the ocean and supplement one's diet.

David: Water in any society, but particularly in isolated island ecosystems, is just critical. In fact, wai is the Hawaiian word for freshwater and waiwai is the Hawaiian word for wealth. So protecting freshwater resources is key, and at Mākua within the valley there are a number of freshwater springs that historically were used by the native Hawaiian communities there and that our clients have been very anxious to ensure are protected from contamination from the live-fire training.

Also key to survival of the local population are the marine resources that are located just offshore of the military reservation. The Waiʻanae coast community is fairly economically depressed, and a lot of the members of the community rely on the ocean for subsistence. They rely on the ocean, either fishing or gathering of limu, which is edible algae, to supplement the diet of their families. And the community was very concerned about the potential for contaminates to be flowing out of Mākua and to contaminate what they considered to be their icebox, their source of food. This is a key component of local culture, native Hawaiian culture, and other cultures that have come to Hawaiʻi, is the ability to gather from the ocean and supplement one's diet.

Kari: What does the valley look like now? Has it changed since the live-fire training has ceased?

David: It's changed dramatically. With the live-fire training in the 1990s when they were doing live-fire training regularly there were literally dozens of fires that would be sparked every year. Some of the fires that resulted in the 1990s were literally thousands of acres burning and so much of the time that the valley was blackened and smoldering.

Now, it's greened up quite a bit. And in addition to that, with the clearance of unexploded ordnance, it's a much safer place. And there is now a cultural life to the valley that was absent before the litigation.

And in terms of what the litigation's done for the future of the valley, when we started the litigation back in the [19]90s, the Army took the position that live-fire training at Mākua was essential to national security. It was irreplaceable and that they would have to continue training at Mākua indefinitely.

Now, over the course of the years as a result of the litigation, there has been no live-fire training at Mākua at all for all but three of the last fourteen years. And during that period of time, particularly from 2001 onward, the soldiers that are stationed in Hawaiʻi have had to repeatedly deploy to combat and they've been able to train and be prepared for that without firing a single bullet at Mākua.

One of the big changes for the valley, I think, as a result of the litigation is that the Army no longer can say with a straight face that training at Mākua was essential. Maybe for them convenient, but certainly not essential. They found alternate places to do that training.

Now the public discourse has moved considerably from, "Gee, we need to let the Army train there. We're concerned about the endangered species and cultural sites, but it's necessary for national security." That was the old discussion. And now the new discussion is, "We're concerned about the endangered species and cultural sites and clearly there are alternatives." And so even the Army has announced plans to renounce live-fire training indefinitely and move elsewhere.

Kari: What are the next steps? What do you expect or wish to happen during your time in court later this month?

David: So after the issuance of the environmental impact statement in 2009, we promptly returned to court because there were key studies that were not completed. One is ensuring the completion of the archeological surveys within the training area that are necessary for both the Army and the public to have a really clear sense of what type of native Hawaiian cultural resources are at risk of being lost forever if the Army did ever resume live-fire training there.

You've got some really unique type of resources at Mākua that lie under the ground, some things that people might not otherwise think of. There are imu, which are earthern ovens where the native Hawaiians would prepare their food. In the valley, right smack dab in the middle of the live-fire training area, they have discovered a series of these imu or earthern ovens that date back to the 14th century. So this provides an important insight into how long people have been living in the valley and where exactly they were living, and what they were doing, and what they were eating. So we're concerned about both the more obvious surface features as well as the subsurface features that provide invaluable information about the cultural history of these people.

The hope is that the Army will finally live up to the promise that it made in 1942 and return the valley to this community.

We established in court that the Army had failed to complete all of the surveys and we're asking the court to order them to conduct those studies. And, in fact, the Army has agreed but they need to actually do those studies.

The second area of inquiry that we challenged was studies of the marine resources on which the local families rely for subsistence: fish, edible algae, shell fish and other resources. We established at trial that the Army had failed to sample many of the resources that were specified in the agreement, leaving the community without any real information about whether they're poisoning their family when they put the stuff on the table.

The limited studies that the Army had done identified levels of arsenic that were off the charts. But then the Army failed to actually determine whether the arsenic that was present in the species they did sample was inorganic, and thus highly toxic, or organic, and relatively benign. These are key questions. The Army had agreed that it would conduct a study to determine the health hazard to both surrounding communities that were eating these resources associated with the training. And then they didn't do very basic inquiries to figure out whether it was a health threat or not.

So the court found that they had violated a number of aspects of the agreement. And so we're returning to court to argue over what the remedy should be for those violations. Fortunately there is a lot of agreement between us and the Army about what the remedy should be. Obviously they need to do those studies. In addition, the Army has agreed that they will not do any live-fire training at Mākua until these studies are completed.

In terms of the way forward, we are anticipating that the Army will comply with the court's order, carry out the studies that are necessary to provide accurate information about the archeological resources that would be at risk from live-fire training, carry out adequate studies to determine the health threat to the surrounding community, and fully digest that information before making any decision about whether live-fire training at Mākua would resume.

Kari: So what do you think the future of the valley looks like?

It's time finally to recognize that a decision that made sense in the wake of Pearl Harbor to do live-fire training in a valley that is full of cultural life and full of endangered species is not a decision that makes sense in the 21st century.

David: The hope is that the Army will finally live up to the promise that it made in 1942 and return the valley to this community. In 1942, they said six months after the cessation of hostilities the valley would be returned. It's time finally to recognize that a decision that made sense in the wake of Pearl Harbor to do live-fire training in a valley that is full of cultural life and full of endangered species is not a decision that makes sense in the 21st century. The Army does have other alternatives for live-fire training that would be far less environmentally and culturally harmful and it's time for them to pursue those, clean the place up, and return it to the people of Hawaiʻi.

Kari: Anything else you'd like to add, David?

David: I think we've done a good job of covering the ground.

Kari: Great! Well, thank you for your time today.